Let's hope his guardians can instill a sense of duty and humillity in him. Still proud as the heir of the Spanish Empire, but tempered.But I also want to see how little Luis Carlos grows. I have a funny feeling he's going to grow up fairly spoiled - especially if his father still dies young, when he's still a minor. Sickly kids often do end up spoiled because the people around them feel sorry for them.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Spanish Heir (What if Carlos II had a son?)

- Thread starter Archduke

- Start date

An interesting idea, timing of the birth is pretty fortuitous. A healthy Spanish heir will doubtless impact Louis XIV's war aims. OTL he kicked of the War of the Reunions by taking Strasbourg and Luxembourg while Vienna was under siege. So I would think Spain is still going to declare war on France as they did OTL now that Vienna is saved. Madrid would have probably have more reason to go to war as they would want to secure the inheritance of the new heir.

On the other hand Vienna had been divided between those who favored looking east to attack the Ottomans and expand into the Balkans and those who favored looking west to confront France and secure the Spanish inheritance. But if the Spanish inheritance is off the table then does that undermine support for the western faction? Likewise for France, if the Spanish inheritance is lost to them would Louis be less inclined to accept a Truce like OTL at Ratisbon that saw him surrender some of his gains in the Spanish Netherlands? Would he instead press on in hopes of gaining as much as he could?

I'm interested to see where this goes.

On the other hand Vienna had been divided between those who favored looking east to attack the Ottomans and expand into the Balkans and those who favored looking west to confront France and secure the Spanish inheritance. But if the Spanish inheritance is off the table then does that undermine support for the western faction? Likewise for France, if the Spanish inheritance is lost to them would Louis be less inclined to accept a Truce like OTL at Ratisbon that saw him surrender some of his gains in the Spanish Netherlands? Would he instead press on in hopes of gaining as much as he could?

I'm interested to see where this goes.

unprincipled peter

Donor

Or Minorca.I wonder what the British will do in this scenario without Gibraltar?

I think Gibraltar was more symbolic than an anchor of security. All the battles and tales of Gibraltar in reality center around Spanish attempts to retrieve it. Never heard of any tales of "we'd have been up poop creek if we didn't have Gibraltar" . Britain didn't do much with it until after the great siege of late 18th century.

Minorca, I believe (don't quote me) had strategic value for trade and a nice deep harbor for a naval base.

Spain also keeps (may lose it along the line) Spanish (OTL Austrian) Netherlands, Milan, Sicily, Naples, and Sardinia.

unprincipled peter

Donor

Much of the last decades of the 17th century was spent jockeying for position in the upcoming Spanish crisis, which here is diverted. War goals and actions will vary with the Spanish succession not a factor.An interesting idea, timing of the birth is pretty fortuitous. A healthy Spanish heir will doubtless impact Louis XIV's war aims. OTL he kicked of the War of the Reunions by taking Strasbourg and Luxembourg while Vienna was under siege. So I would think Spain is still going to declare war on France as they did OTL now that Vienna is saved. Madrid would have probably have more reason to go to war as they would want to secure the inheritance of the new heir.

On the other hand Vienna had been divided between those who favored looking east to attack the Ottomans and expand into the Balkans and those who favored looking west to confront France and secure the Spanish inheritance. But if the Spanish inheritance is off the table then does that undermine support for the western faction? Likewise for France, if the Spanish inheritance is lost to them would Louis be less inclined to accept a Truce like OTL at Ratisbon that saw him surrender some of his gains in the Spanish Netherlands? Would he instead press on in hopes of gaining as much as he could?

I'm interested to see where this goes.

So it is very likely that the French starting the next war against Spain for the Netherlands will be the big European event at the beginning of the new century, obviously the Spanish will want to secure the inheritance of Louis Charles and not lose their most profitable territorial possession, however it would be interesting to see what effects the Netherlands still under Spanish rule would have on the rest of the empire.

The Austrians on the other hand will be busy fighting the Ottomans while waiting to see if the war of Polish succession (1733-1738) occurs.

The Austrians on the other hand will be busy fighting the Ottomans while waiting to see if the war of Polish succession (1733-1738) occurs.

Last edited:

unprincipled peter

Donor

Have to get through the 9 years war first. The ending of that one was heavily impacted by the wide held belief that the childless Carlos II was near death. Here, there's an heir. France ended the war with an eye to regroup for the WoSS. Here, with the coalition against them splintering, France may press on for a little more gain.So it is very likely that the French starting the next war against Spain for the Netherlands will be the big European event at the beginning of the new century, obviously the Spanish will want to secure the inheritance of Louis Charles and not lose their most profitable territorial possession, however it would be interesting to see what effects the Netherlands still under Spanish rule would have on the rest of the empire.

The Austrians on the other hand will be busy fighting the Ottomans while waiting to see if the war of Polish succession (1733-1738) occurs.

Plus, I don't think Spanish Netherlands was such a big target any more. War of Reunions and 9YW were about solidifying French territory, not taking Spanish Netherlands. Had things gone better for France in 9YW, SN might have ended up French, but they weren't the goal when the war started. Then, in the WoSS, France offered up the SN to Max Emanuel of Bavaria for his help in taking Spain for Philip.

The most profitable part of Spain is likely the American colonies, although maybe the gold/silver hasn't started pouring in yet.

You may be right, the colonies in the Americas have for a long time been the most profitable possessions but it is over a period of time that corruption, piracy and mainly the worn out extractive model prevents them from being as profitable as they should be in comparison to Netherlands. Once the Spanish start to reform you can see them taking some ideas from the Dutch and adapting them.The most profitable part of Spain is likely the American colonies, although maybe the gold/silver hasn't started pouring in yet.

Last edited:

Well the Netherlands will be a pressing issue in so much as the French have already occupied Luxembourg under their policy of Reunion. Both Luxembourg and Strasbourg were occupied prior to the birth of Luis Carlos which is what prompted Spain to go to war IOTL officially starting the War of the Reunions. So that will have to be addressed in one way or another. Spain won't want to concede Luxembourg and the Emperor will be concerned with the occupation of Strasbourg as an Imperial Free City.

As for the colonies France had been eyeing them for a while. The 1669 Partition Treaty between Leopold and Louis assigned the Philippines to France. But that was when Colbert was trying to setup up the French East India Co. With New France expanding in the late 1600s and France having gained a toe hold in Saint Domingue they could instead shift their interest to the Spanish Americas.

As for the colonies France had been eyeing them for a while. The 1669 Partition Treaty between Leopold and Louis assigned the Philippines to France. But that was when Colbert was trying to setup up the French East India Co. With New France expanding in the late 1600s and France having gained a toe hold in Saint Domingue they could instead shift their interest to the Spanish Americas.

unprincipled peter

Donor

Were the Spanish Netherlands all that profitable? I thought Austria didn't really want them and treated them as an afterthought? France wanted them for security purposes, and was willing to let Bavaria have them in WoSS. England/Britain and Dutch didn't want the Bourbons to have them for security purposes, but never really tried to take them.

My impression, aside from the military factor, was that they were mildly profitable, but not any sort of cash cow.

Certainly, when you had up the Spanish losses - Netherlands, Sicily, Naples, Sardinia, Milan - various sources of income were gone.

My impression, aside from the military factor, was that they were mildly profitable, but not any sort of cash cow.

Certainly, when you had up the Spanish losses - Netherlands, Sicily, Naples, Sardinia, Milan - various sources of income were gone.

unprincipled peter

Donor

Yup. A continued Habsburg Spain puts the colonies as fair game during future conflicts.Well the Netherlands will be a pressing issue in so much as the French have already occupied Luxembourg under their policy of Reunion. Both Luxembourg and Strasbourg were occupied prior to the birth of Luis Carlos which is what prompted Spain to go to war IOTL officially starting the War of the Reunions. So that will have to be addressed in one way or another. Spain won't want to concede Luxembourg and the Emperor will be concerned with the occupation of Strasbourg as an Imperial Free City.

As for the colonies France had been eyeing them for a while. The 1669 Partition Treaty between Leopold and Louis assigned the Philippines to France. But that was when Colbert was trying to setup up the French East India Co. With New France expanding in the late 1600s and France having gained a toe hold in Saint Domingue they could instead shift their interest to the Spanish Americas.

Were the Spanish Netherlands all that profitable? I thought Austria didn't really want them and treated them as an afterthought? France wanted them for security purposes, and was willing to let Bavaria have them in WoSS. England/Britain and Dutch didn't want the Bourbons to have them for security purposes, but never really tried to take them.

My impression, aside from the military factor, was that they were mildly profitable, but not any sort of cash cow.

Certainly, when you had up the Spanish losses - Netherlands, Sicily, Naples, Sardinia, Milan - various sources of income were gone.

Pretty much. They didn't bring in much money so once you take into account the massive cost of the Army of Flanders it was a huge money sink for Castile. Leopold was content to give them to France when he arranged a partition of the Spanish inheritance will Louis in the 1660s. He wanted Spain and Spanish Italy. But the English and Dutch didn't want France to get the Spanish Netherlands hence later Anglo-French Partition treaties assigned them to the Austrians.

IMHO Spain would have been better off divesting itself of the Netherlands but through the reign of Philip IV its policy was still driven by reputacion and so its strategic imperative was essentially to maintain the appearance of strength and avoid concessions that would suggest weakness. Though in fairness, allowing the southern Netherlands to fall into Spanish hands and strengthen the hand of Spain's mortal enemy would not be strategically wise either. If Louis secured his northern flank he'd probably just focus his energies on Spanish Italy.

Spanish Italy was mostly self supporting, at least in peace time. The Regno provided the bulk of the men and money for the Army of Italy (Milan). Sicily and Milan itself provided the rest. Of course during the Franco-Spanish war the cost was too high and Castile had to make up the difference. The problem in the latter half of the 17th century is that Naples had been so devastated by war and plague that the incomes of the Regno were greatly diminished and the whole system began to crumble though the situation is not irretrievable.

After reviewing this period, I agree that the best thing to do would be to hand over the Netherlands to Austria, leaving Spain to concentrate on the Mediterranean and the Colonies.

With regard to the colonies, the Spanish may be improving their position by fortifying strategic points throughout the colonies while taking measures to develop them by opening them up to trade and immigration from the rest of the Catholic world after settling the problems at home.

With regard to the colonies, the Spanish may be improving their position by fortifying strategic points throughout the colonies while taking measures to develop them by opening them up to trade and immigration from the rest of the Catholic world after settling the problems at home.

Last edited:

Is there any chance keeping Naples as part of the Spanish empire would allow it to recover to it's pre plague population of 300,000 quicker through continued immigration from Spanish territories?

Even if it can't consistently keep up with Paris (which was also about that size in the mid 1600s) say it gets to 450,000 by the early 1700s roughly three times the size of Madrid.

what are the effects of Naples cementing itself as the largest city/cultural capital of the Spanish empire?

Faced with difficulties modernising the finances of Spain, and perhaps with Naples being larger perhaps a future enlightened king could help transform it into the financial hub of the Mediterranean. In any case, keeping Naples strengthens the idea of the Spanish empire being kingdoms all loyal to the Spanish king than just all being colonies of Spain- and as Spanish can't be enforced in Naples, it's less likely to be enforced in Catalonia either.

Even if it can't consistently keep up with Paris (which was also about that size in the mid 1600s) say it gets to 450,000 by the early 1700s roughly three times the size of Madrid.

what are the effects of Naples cementing itself as the largest city/cultural capital of the Spanish empire?

Faced with difficulties modernising the finances of Spain, and perhaps with Naples being larger perhaps a future enlightened king could help transform it into the financial hub of the Mediterranean. In any case, keeping Naples strengthens the idea of the Spanish empire being kingdoms all loyal to the Spanish king than just all being colonies of Spain- and as Spanish can't be enforced in Naples, it's less likely to be enforced in Catalonia either.

Last edited:

When and how?keeping Naples as part of the Spanish empire

They don't lose it? If we're butterflying the war of Spanish succession, luis Carlos should just inherit it.When and how?

The growth in the cities population otl mainly came from Spanish territories in the 16th and 17th century, so without severing that link it should remain the premier destination for people looking to make an urban lifestyle from everywhere ruled by the Spanish king.

Interesting question, Luis Carlos is the grand-nephew of James II of England as the grandson of Minette. In fact, after the mainline Stuarts, he is the next in line to the English throne. So Luis Carlos does have some interest in supporting James II. To be fair, even Christian V, the brother of Prince George of Denmark, Anne's husband, was also disinclined to the Glorious Revolution just to his revulsion toward usurping a fellow monarch. So Luis Carlos might be in the same boat as Christian V if he finds himself reliant on the support of Willem van Oranje.Without the war of the Spanish succession

Could we see Spanish support for James III or at least a second Armada?

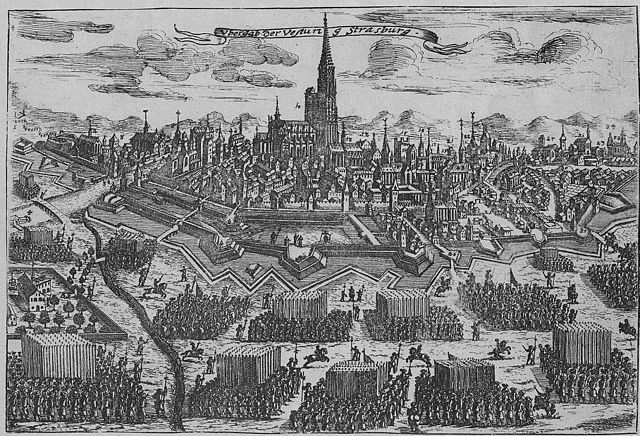

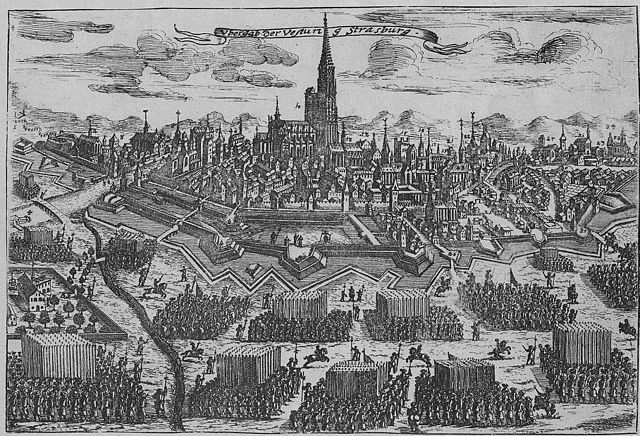

1.3: Chambers of Reunions

III: Chambers of Reunions

Capture of Strasbourg (1681)

Capture of Strasbourg (1681)

The appearance of a Spanish heir represented a massive change in Europe's politics. Even with Louis XIV's wars of expansion and the Ottoman-Austrian wars, the biggest question in Europe's politics for the past two decades had always been the Spanish succession. The expectation of Carlos II's death without children had been a powerful driving force in European diplomacy. In 1668, even with the Triple Alliance of England, the Dutch Republic, and Sweden threatening France, the deciding factor in Louis XIV's decision to end the War of Devolution was rumours of Carlos II's imminent death. If Carlos II died, Louis XIV expected that war would no longer be necessary to bring the Spanish Netherlands into the folds of France. That same belief in Carlos II's death had brought about a temporary reconciliation between France and the Austrian Habsburgs whereby the Austrian Habsburgs would stay aside as France punished the Dutch Republic. In return, France and Austria would amicably split the Spanish empire between themselves. Meanwhile, the Dutch had ended decades of hostility toward the Spanish because they feared the thought of France inheriting the Spanish fortresses that separated the Republic from France. So much of European thinking revolved around the idea of a childless Carlos II.

Even when Marie Louise became visibly pregnant, Europe remained doubtful. Many recalled how just as soon as Carlos II was born, he fell violently ill and very nearly lost his life. That illness left Carlos II vulnerable to a life of more near-deadly encounters. The possibility that Carlos II's son would suffer the same fate was not regarded as unlikely. Meanwhile, Marie Louise was one of just three successful pregnancies that her mother had. Of the other five, four were miscarriages and one was stillborn. This history did not bode well for Marie Louise and given the almost complete vitality of the father, many European diplomats and politicians expected Marie Louise's pregnancy to fail. Only during the last weeks of Marie Louise's pregnancy did Europe's courts begin to truly contemplate the possibility of a Spanish heir. They were still trying to wrap their heads around a thought that had not bothered them for two decades when Luis Carlos was born.

In the weeks following Luis Carlos's birth, Europe looked on suspiciously and anxiously to see if the boy would suffer his father's fate or would defy all odds and indicate good health. The news of Louis Carlos's ill health paused the adaptation of strategic thinking toward Spain. But, just like France and Austria, the rest of Europe began to settle into the idea of a Spanish heir after Luis Carlos had survived his first month. A stable and uninhibited Spanish succession preempted a partition of the Spanish empire. For the rulers who had sought to gain from that partition, Luis Carlos denied them easy gains and they now had to decide whether they would still pursue those gains through the use of arms or if they would turn their sights elsewhere. Those who had feared their enemies would benefit from Spain's partition and acted to defend Spain from that fate, now found themselves wondering if they still needed to stand by Spain or if Spain was actually the enemy now.

To add to this uncertainty, the birth of Luis Carlos coincided with the crushing Christian relief at Vienna. Although the Ottoman threat in theory was more than two and half centuries old, an Ottoman army being on the verge of capturing Vienna was a less familiar concept. However, for close to two months, an Ottoman victory at Vienna had seemed almost certain as the Austrians lacked the manpower to resist the Ottomans on their own and many of the German princes refused to come to Vienna's aid cheaply. Only the generous offer of Maximilian Emanuel II to provide his army almost freely and King Jan III Sobieski's willingness to leave Poland undefended while he galloped toward Vienna had enabled the stunning Christian victory. Without either of them, the Christians surely would not have had enough men to overcome the Ottomans.

Once they had that manpower, however, the Austrians could not help but feel as if the road to Buda or even to Constantinople was wide open. To them, the victory at Vienna seemed like a sign from God that the time had come to reclaim Hungary and the Balkans from the Muslim Turks. From a more practical standpoint, the Christian victory had put the Ottoman army into complete disarray. In its broken state, even with its immense size, the Christians did not expect the Ottoman army to be able to hold up against a determined Christian attack. Thus, the image of a ruined Vienna and an Austria opened wide to the depredations of the Ottomans had been replaced with the possibility of an Austrian recovery of Hungary that greatly doubled the size and population of the Austrian Habsburg realm. At the same time, the victory at Vienna might allow Poland-Lithuania to recover the lands it lost to the Ottomans in 1676. The prospect of Austria and Poland overseeing their own versions of a Reconquista threatened to shake up European politics just as much as the birth of Luis Carlos did.

The country that was most threatened by these parallel developments was France. Over the last two decades, France and its King, Louis XIV, had waged two wars of expansion with a focus on rationalizing the borders of France. These wars had brought France into conflict with the Spanish empire and the Holy Roman Empire which held several of the bordering territories that France sought to conquer. The superiority of France’s armies and the brilliance of its commanders resulted in France winning those conflicts and embarrassing the armies of both Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. The birth of a Spanish heir and the Austrian victory at Vienna did not break France’s superiority but they jeopardized it by instilling new confidence and stability in Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. In Spain, the miracle of Luis Carlos’s birth became a rallying point for talk about Spanish resurgence. Additionally, with a Spanish heir, the French and Austrian factions that had developed to dispute the succession fell apart. Instead, the Spaniards regrouped around their own national policy and interests, to the dismay of France. At the same time, the dramatic victory at Vienna made the Austrians believe in the strength of their arms, even if their own army was carried by the efforts of Poland, Bavaria, and Saxony. This belief was strong enough that the advisers surrounding Emperor Leopold began to talk about how after Austria overcame the Ottoman threat that it could take its battle-hardened and victorious army to Western Europe where it could restore the Imperial borders. Furthermore, even though Austria had needed the help of the Imperial princes to save itself, the bloody battle at Vienna had forged many bonds between those Imperial princes and their Emperor. The prospect of further glory in the name of the Holy Roman Empire excited many of the Imperial princes. Max Emanuel of Bavaria who spoke French just as much as he spoke German was a prime example of this phenomenon. Thus, these two developments emboldened and solidified two of France’s primary enemies.

With France’s own growing strength, Louis XIV might have tried to outstrip a potential Spanish resurgence and Austrian expansion. Also, it remained entirely possible that Luis Carlos would die and that Spain would be thrown into political and diplomatic turmoil once again. Meanwhile, the Ottomans who had just been knocking on the doorsteps of Vienna might regroup and reverse the tides of war with the Austrians. However, Louis XIV and his advisers did not think it was likely for them to be so fortunate. Additionally, even if France might outgrow or outlast these surges in Spain and Austria, the fact remained that for the time being France had an enormous advantage over either state. If France waited, even if France remained at an advantage, it was unlikely to be as massive as the one it currently held. If France wanted to ensure the easiest triumph over Spain or Austria then it was much better to strike early.

This mindset led Louis XIV to revive his policy of Reunions against Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. This policy had involved using French courts to lay claim to parts of the Spanish Netherlands and the Holy Roman Empire. Taking advantage of vague treaties, ancient rights, and poorly demarcated borders, the Chambers of Reunions had conjured up France claims that the French army under General Louis Francois de Boufflers had enforced. The relative weakness of the Spanish and Imperial forces to the north and east of France had meant that General Boufflers overran any opposition before him. Through these means, the French gobbled away at Alsace, Zweibrucken, Saarbrucken, Veldenz, Montbeliard, and more. In 1681, the French even occupied the city of Strasbourg. Even though they proclaimed Strasbourg to be a neutral city, it was clear to all that it and all of Alsace had been conquered by France. Next, the French laid siege to Luxembourg so that they could turn that great fortress into the anchor of their new border. Ultimately, the growing hostility between the Ottomans and the Austrians in 1682 had stayed the hand of France. Louis XIV consisted it unchristian to continue to use arms against other Catholics while an Ottoman army bore down on the Holy Roman Empire and lifted the Siege of Luxembourg in March, 1682. As a condition for ending his siege of Luxemburg, Louis XIV also demanded that Spain accede to the arbitration of France’s claims to Luxembourg overseen by the King of England. Of course, Louis XIV’s willingness to stand down his armies did not stop him from providing monetary support to the Ottomans as they crossed into Austria and laid siege to Vienna.

After September 12, 1683, Louis XIV no longer held the same view. With the Ottoman army summarily repulsed, Louis XIV no longer felt any reason to restrain himself from quarreling with Spain or the Holy Roman Empire. Additionally, with the above-mentioned stabilizations for Spain and Austria, Louis XIV felt a sense of urgency to act against the two states. By reactivating his Reunions strategy, Louis XIV sought to fulfill the wrap up of the border rationalization he had begun. Most importantly, Louis XIV wanted to conquer Luxembourg so that its critical fortress could become a bulwark of France rather than remain a forward base of his enemies. Under this framework, General Boufflers army was put on the move again. Accompanying the re-mobilization of General Boufflers’s 35,000 men, Louis XIV informed the Spanish governor of the Southern Netherlands, Ottone Enrico del Caretto, Marquis of Grana, that Spain would have to provide the army of Boufflers with 3,000,000 florins to sustain it once it crossed the border. The justification that Louis XIV offered for this invasion was that Spain had failed to agree to the arbitration and thus left Louis XIV no choice but to assert his claims through the use of arms.

For Spain, this imminent invasion of the Spanish Netherlands and the demands of Louis XIV were finally too much. Immediately, orders were dispatched for Grana to meet the French invasion with force, even though the field army he commanded was less than half the size of the army of Boufflers. Grana at least was smart enough to avoid matching Boufflers’s army directly. Instead, Grana sent raids against French villages along the border where the Spanish soldiers coerced contributions of money and food out of the French peasants. Louis XIV did not take these raids well and ordered the most vicious retaliation. Specifically, Louis commanded Marechal d'Humieres “to burn fifty houses or villages for everyone which will have been burned on my lands”. Louis XIV had no tolerance for the resistance of the Spanish and wished to break their nascent confidence as quickly as possible.

The invasion of Boufflers and the quickly escalating tit-for-tat in the Low Countries did not intimate Spain as Louis XIV might have desired. Instead, the Spanish decided that they could no longer sit back and allow France to abuse them freely, without consequence. Spain’s time to make a decisive stand against France had come. So on November 11, 1683, the Spanish government delivered a declaration of war to the French minister in Spain. According to this document, the Spanish accused the French of regularly trespassing into Spanish territory, seizing Spanish towns, and robbing Spanish citizens. All of these accusations were of course completely valid. Outside of these accusations, the Spanish made it clear to the French minister that their intention was to reclaim the lands that the French had unjustly seized in the past four years, but the Spanish even dared to intimate that they would go further and reconquer the lands lost since the Treaty of the Pyrenees.

Although much talk has been made of the impact that Luis Carlos’s birth had on the confidence of Spain, Spain’s willingness to unilaterally declare war on the far stronger France should not be credited solely to Luis Carlos’s birth. Indeed, the path toward Spain’s declaration of war began well-before Luis Carlos’s birth and even before his conception. Since 1679, when France first began to use legal arguments to violate the peace of Nijmegen, the Spanish government had been trying to design a means of stopping the French advances into their territory. This response saw Spain attempt to increase the size of the Army of Flanders through local recruiting, redeployments from Spain, and from the purchasing of German auxiliaries. However, the limits of Spain’s fledging economy prevented Spain from making a massive increase in the Army of Flanders before Boufflers’s invasion. Instead of either Luis Carlos’s birth or the reinforcing of the Army of Flanders being the impetus for Spain’s declaration of war, it was diplomatic success that made the Spaniards believe that opposing the French in an open war was a realistic option.

Throughout 1683, the Spanish diplomats at the Hague discussed at length the idea of an anti-French alliance with the Dutch stadtholder, Willem van Oranje. Willem like the Spanish was greatly concerned by the growing power of France and felt threatened by the French encroachments on Spanish territory. Willem’s vivid memories of the French invasion of the Dutch Republic in 1672 made him greatly concerned by the idea of the French swallowing up pieces of the Spanish Netherlands and steadily diminishing the buffer between France and the Dutch Republic. Besides this sense of fear, Willem’s own belief in himself led him to think that he could defeat France if the Staten-Generaal would give him the money and men to do so. Although the Dutch Republic had not won the 1672 war against France, it had turned the French back and prevented a total defeat. In the next war, Willem imagined that he would do better.

Although Willem was quickly convinced of the viability and smartness of an alliance with Spain, many of the Dutch politicians did not feel the same. Although some were concerned by the weakness and fragility of Spain, for most the greater issue was the overwhelming strength of France. During the last war, the Spanish had managed to build an army of more than 50,000 men to contest the Spanish Netherlands with France, but France had more than 100,000 thousand men and successfully fought its enemies from Sicily to Flanders. France was a monstrous enemy and was not one that should be reckoned with. Only months of carousing and bullying from Willem and the Spanish diplomats resulted in the Staten-Generaal’s reluctance to an alliance being overcome. Finally, in autumn, just before the birth of Luis Carlos, the Dutch Republic and Spain signed an alliance to defend one another against France. With this alliance backing Spain and with messages of support from the Holy Roman Emperor and Sweden, Spain thought that it had the necessary tools to resist France in late 1683 and confidently marched into a war against the best and biggest army in Europe.

Last edited:

Share: